An exploration of the conductor's second cycle of Mahler symphonies.

by Paul J. Pelkonen

Leonard Bernstein's 100th birthday (August 25th of this year) has been met with performances and festival devoted to his musical output. However, it could be argued that his achievements as a conductor are as important as his compositions. With thirty years of recordings to choose from, which makes it necessary to choose a microcosm from which one can generate a judgment. For these purposes, that microcosm will be Bernstein's late recordings of the symphonies of Gustav Mahler, made in the last decade of his life.

Bernstein made his first Mahler cycle (for Columbia) from 1960-1975, beginning the project during his term at the helm of the New York Philharmonic. These remakes were inspired by the conductor's passion for Mahler's music and the Deutsche Grammophon label's enthusiasm for the compact disc and digital recording techniques. The cycle was made with three international orchestras: the New York Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. Each of these ensembles has a rich history with Mahler's music. These are records based on live performances, with conductor, orchestra and the DG tonmeister occasionally sessioning to fix a minor error.

The Symphony No. 1 was recorded in Amsterdam on October 10, 1987. This four-movement work did much to establish Mahler's compositional voice and polyglot musical style. From the first descending intervals, Bernstein conjures an airy, misty atmosphere, from which birdcalls, distant, staccato trumpets and finally, a breezy little melody. This yields to a series of other ideas (that evoke childhood innocence. (Mahler makes memorable use here of a theme from Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel, the children's belief that the menacing voice of the Witch is nothing more than the wind in the trees.) Eventually the offstage horn chorales are very much present in the trumpets and onstage brass, and the noble theme is played full out, reaching an exultant close.

Bernstein's precise control of his forces is best heard in the second movement. Here, the plodding rhythm churned by the cellos and basses has a certain lightness to it. He achieves this through rubato, borrowing an extra fragment of a beat to stretch a rest or make the music breathe like a living thing. That sense of breath is picked up by the woodwinds in their call-and-response answer to the cellos. The trio is taken very slowly, with Bernstein milking each note for its full value, suggesting at once summer torpor and unbearably sweet nostalgia. The schlag is thick here.

The slow movement is the least spectacular, but the one that quantifies the idea of laughter through tears. It is a somber, lugubrious and yet humorous funeral procession: the portrait of a slain hunter being carried to his eternal rest by the (relieved and celebrating) animals of the forest. Mahler quotes the tune "Bruder Martin" (better known to Anglophones as "Frére Jacques") as the main theme of his little march. It yields to what can only be described as a wedding celebration. The music gains a manic playfulness as if the musicians were slightly drunk, before re-settling into the funeral procession.

Conductor and orchestra are at their most mutually exuberant in the final movement. This is a huge double structure, a triumphant structure that can easily devolve into tedium and bombast. It starts with a crash of cymbals and a shattering dissonant chord. The orchestra charges forward into the upward brass theme from the first movement, but with a new intensity. Chugging strings push the music forward and the rondo theme starts, an answer to the questions posed in the first movement.

Mahler and Bernstein do not just answer the question: they show all of their work in their quest to achieve a kind of musical elevation. Much of the lifting is done by the horns, who (as performance tradition dictates) are standing by the end of the movement with the bells of their instruments lifted into the air. The other sections toss the musical ideas back and forth, with the whole building to a series of climaxes. Trumpets and trombones join the fray, a suggestion of the higher powers that will be confronted in the subsequent symphonies of the cycle.

by Paul J. Pelkonen

|

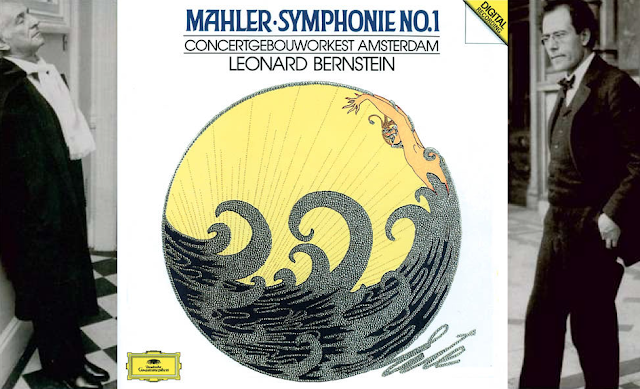

| Combination of cover art from two different pressings of the Mahler Symphony No. 1. Drawing by Erte, photographs © 1989 Deutsche Grammophon/Universal Classics. |

Bernstein made his first Mahler cycle (for Columbia) from 1960-1975, beginning the project during his term at the helm of the New York Philharmonic. These remakes were inspired by the conductor's passion for Mahler's music and the Deutsche Grammophon label's enthusiasm for the compact disc and digital recording techniques. The cycle was made with three international orchestras: the New York Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. Each of these ensembles has a rich history with Mahler's music. These are records based on live performances, with conductor, orchestra and the DG tonmeister occasionally sessioning to fix a minor error.

The Symphony No. 1 was recorded in Amsterdam on October 10, 1987. This four-movement work did much to establish Mahler's compositional voice and polyglot musical style. From the first descending intervals, Bernstein conjures an airy, misty atmosphere, from which birdcalls, distant, staccato trumpets and finally, a breezy little melody. This yields to a series of other ideas (that evoke childhood innocence. (Mahler makes memorable use here of a theme from Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel, the children's belief that the menacing voice of the Witch is nothing more than the wind in the trees.) Eventually the offstage horn chorales are very much present in the trumpets and onstage brass, and the noble theme is played full out, reaching an exultant close.

Bernstein's precise control of his forces is best heard in the second movement. Here, the plodding rhythm churned by the cellos and basses has a certain lightness to it. He achieves this through rubato, borrowing an extra fragment of a beat to stretch a rest or make the music breathe like a living thing. That sense of breath is picked up by the woodwinds in their call-and-response answer to the cellos. The trio is taken very slowly, with Bernstein milking each note for its full value, suggesting at once summer torpor and unbearably sweet nostalgia. The schlag is thick here.

The slow movement is the least spectacular, but the one that quantifies the idea of laughter through tears. It is a somber, lugubrious and yet humorous funeral procession: the portrait of a slain hunter being carried to his eternal rest by the (relieved and celebrating) animals of the forest. Mahler quotes the tune "Bruder Martin" (better known to Anglophones as "Frére Jacques") as the main theme of his little march. It yields to what can only be described as a wedding celebration. The music gains a manic playfulness as if the musicians were slightly drunk, before re-settling into the funeral procession.

Conductor and orchestra are at their most mutually exuberant in the final movement. This is a huge double structure, a triumphant structure that can easily devolve into tedium and bombast. It starts with a crash of cymbals and a shattering dissonant chord. The orchestra charges forward into the upward brass theme from the first movement, but with a new intensity. Chugging strings push the music forward and the rondo theme starts, an answer to the questions posed in the first movement.

Mahler and Bernstein do not just answer the question: they show all of their work in their quest to achieve a kind of musical elevation. Much of the lifting is done by the horns, who (as performance tradition dictates) are standing by the end of the movement with the bells of their instruments lifted into the air. The other sections toss the musical ideas back and forth, with the whole building to a series of climaxes. Trumpets and trombones join the fray, a suggestion of the higher powers that will be confronted in the subsequent symphonies of the cycle.