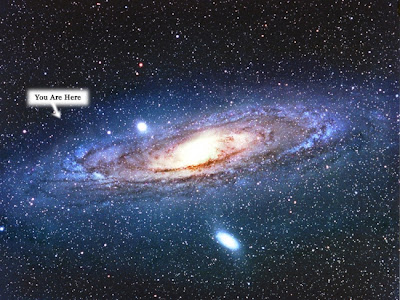

|

| Bruckner's music puts everything in perspective for the listener. With thanks to Douglas Adams for the idea. |

The main reason for this was the presence of violinist Leila Josefowicz. The Canadian soloist stunned the audience with her fearless, fleet interpretation of Mr. Adams' three-movement violin concerto, a treacherous composition from the pen of the composer of Nixon in China. Placed next to the Bruckner, the influence of one composer on the other was clear, creating the fresh perspective that is Mr. Welser-Möst's intent.

This concerto is written on a large scale, with a long difficult solo part that never seems to yield the stage to the orchestra. Ms. Josefowicz tore eagerly into the opening movement, and produced sweet lyric tone in the long, slow chaconne. Mr. Welser-Möst accompanied the soloist with a sensitivity, keeping the pace of the chaconne smooth and flowing, with a slow circular groove that was almost percussive in its steadiness.

Ms. Josefowicz displayed astounding technique in the final movement, racing over the chugging ostinato rhythms with such force that she shredded the horse-hair on her bow. Without missing a beat, she conducted a swift bow repair and raced to the finish line of the piece. It was a bravura monologue for this talented soloist, the kind of reading that makes a good case for further exploration of Mr. Adams' music by the most conservative music lover.

Bruckner's Seventh Symphony is the composer's most popular work, the piece which "broke" him with the Viennese public and finally earned the grudging respect of critic Eduard Hanslick. The Seventh is written on the same large scale as the other late Bruckner works, with the addition of four Wagner tubas to the brass choir. This is a hybrid of horn and tuba, invented by Wagner for the first performances of his own Der Ring des Nibelungen.

The Seventh builds to a series of slow, relentless climaxes before pausing and building again, rising to a mighty height at the end of its first movement. The coda of the opening Sonata Allegro pays homage to Wagner himself, with the entire 13-strong brass section playing a chorale that sounds like the opening of Das Rheingold played backward. It is an astonishing effect.

|

| Anton Bruckner. |

The third movement, a bucolic series of Austrian peasant dances, allowed the conductor and orchestra to show their playful sides. Woodwinds and strings whirled and stomped through the trio section, in the form of a Ländler, a kind of Austrian Alpine hoedown. Mr. Welser-Möst displayed mastery of the tricky triple-double "Bruckner rhythm" that dominates this movement.

The finale elevated the listener back to the heights of Bruckner's sonic mountain, with a return of the opening brass chorale and a new theme developed within the woodwinds. At the work's climax, the backward Wagnerian chorale returned, leaving the listener on the windy heights, under the starry vault, marvelling at the scope of Bruckner's creation. It was a stirring end to the second New York concert by this fine orchestra, who were in excellent playing form and inspired by the exceptional material in front of them.

Bruckner (r)Evolution concludes this weekend with the Eighth and Ninth Symphonies. Tickets are available through Lincoln Center Festival.