Some thoughts on Berlioz' Symphonie Fantastique.

by Paul J. Pelkonen

If you've read Superconductor since the beginning you know that this blog has spent a lot of column length on the music of Hector Berlioz. Berlioz was an author and a music critic (much like your humble narrator.) He was also a revolutionary and romantic composer who cut an eccentric but fearless path through the cutthroat world of the Paris music scene in his lifetime. His Symphonie-fantastique, which burst upon the world in 1829, was one of the reasons for the rise of program music in the 19th century. Even more revolutionary was his use of a recurring motif or idée-fixe, whose development over the course of five movements predicted the Wagnerian idea of leitmotif.

The fiery composer wrote the Fantastique as a means of processing his feelings about one Harriet Smithson, an Irish actress he saw in an English-language production of Hamlet in 1827. Smitten, he sent her letters, which she apparently ignored. Less attractively, he rented an apartment across from her lodgings so he could observe her returning home from the theater. Thankfully, he also worked, sketching the Symphonie-fantastique apparently as a means of processing the emotions he was feeling from his infatuation. (For the record, she married him in 1833, but it was an unhappy and short-lived union.)

Its five movements are like nothing that came before it in music. Beethoven had dabbled in the idea of programmatic symphony, putting titles to the movements of his Pastorale. It was Berlioz who took the idea to its logical summation, writing down a detailed program of the poor unfortunate subject of his work, a love-struck artist who was naturally, the composer himself. The first three movements deal with the early stages of an imagined relationship: the ecstasy of first meeting the reverie of social interaction and the inevitable letdown and emotional isolation that follows.

How Berlioz' imaginary protagonist deals with that isolation is what makes this work so memorable. The artist indulges in opium, (rather too much of it) and has a pair of phantasmic dreams, "bad trips" if you will, where he undergoes horrors that are portayed by the huge orchestra with gleeful abandon. The first of these is a March to the Scaffold, a driving thrust of a movement that ends in the main theme of the work being literally decapitated in mid-phrase. This is followed by the Dream of a Witch's Sabbath, an inspiration for every horror-movie composer of the 20th century and a terrifying experience with the right conductor.

For the purposes of this article, the recording listened to was a 1997 set made by Pierre Boulez and the Cleveland Orchestra. This taut, hard-edged recording, in controlled conditions and crisp digital sound, seems like it would be a contradiction in musical terms. It is led by a composer-conductor who is on the record as not being a particular admirer of Berlioz, seemed intent on making the point that the music written in this work was far ahead of its time. And he's right. Berlioz set the template here for a lot of French romantic music that followed, and his influence can be heard as far forward as works like Ravel's La valse and the ballet scores of Igor Stravinsky.

The Cleveland players take a crisp and modern approach to this score, only occasionally opting for period sound for certain effects. Most notable are the surging strings and winds in Reveries-passions, the first movement, and the glittering harps that adorn Un bal. With slow tempos, Boulez achieves a kind of existential loneliness in the slow movement, as the piping shepherds anticipate the bleak third act of Wagner's Tristan. The passage of the March to the Scaffold where the clomping strings are repeatedly interrupted by a merry band of brass players (complete with the blatting of the ophicleide) points the way forward to the controlled musical anarchy of Strauss' Till Eulenspiegel and Stravinsky's Petrushka.

In the final movement, Boulez emphasizes the horrifying transformation that Berlioz wreaks on the idée-fixe. His orchestra grimaces, leaps and leers where it first capered and whirled. Any possible love left between the Artist and his intended is obliterated by the grim tones of the Dies Irae and the capering woodwind section, which itself plays a fairground parody of that medieval hymn. It is as if the demonic laughter cannot control itself. The finale, which combines the now twisted and thoroughly wrecked Dies Irae idea with the idée-fixetheme that has coursed throughout the five movements. These two twisted ideas battle like wrestling snakes, creating an unwholesome gestalt that surges, rises and clatters to an apocalyptic finish. Music would never be the same.

Did you enjoy this review? Then why not pop over to Superconductor's Patreon page and support the cause of independent arts journalism today.

by Paul J. Pelkonen

| |

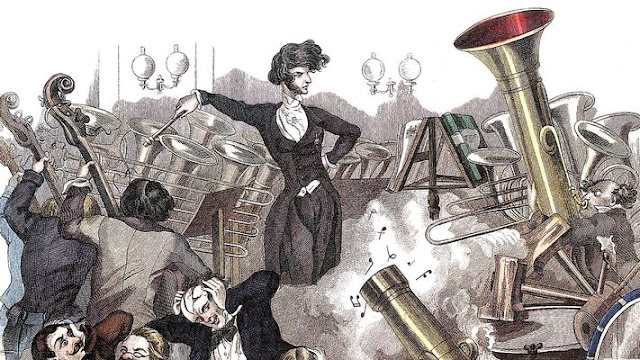

| Detail from a caricature of Hector Berlioz by Anton Elfinger. The caption read: "Heureusement la salle est solide... elle résiste." © 1982 University of Chicago Press. |

The fiery composer wrote the Fantastique as a means of processing his feelings about one Harriet Smithson, an Irish actress he saw in an English-language production of Hamlet in 1827. Smitten, he sent her letters, which she apparently ignored. Less attractively, he rented an apartment across from her lodgings so he could observe her returning home from the theater. Thankfully, he also worked, sketching the Symphonie-fantastique apparently as a means of processing the emotions he was feeling from his infatuation. (For the record, she married him in 1833, but it was an unhappy and short-lived union.)

Its five movements are like nothing that came before it in music. Beethoven had dabbled in the idea of programmatic symphony, putting titles to the movements of his Pastorale. It was Berlioz who took the idea to its logical summation, writing down a detailed program of the poor unfortunate subject of his work, a love-struck artist who was naturally, the composer himself. The first three movements deal with the early stages of an imagined relationship: the ecstasy of first meeting the reverie of social interaction and the inevitable letdown and emotional isolation that follows.

How Berlioz' imaginary protagonist deals with that isolation is what makes this work so memorable. The artist indulges in opium, (rather too much of it) and has a pair of phantasmic dreams, "bad trips" if you will, where he undergoes horrors that are portayed by the huge orchestra with gleeful abandon. The first of these is a March to the Scaffold, a driving thrust of a movement that ends in the main theme of the work being literally decapitated in mid-phrase. This is followed by the Dream of a Witch's Sabbath, an inspiration for every horror-movie composer of the 20th century and a terrifying experience with the right conductor.

For the purposes of this article, the recording listened to was a 1997 set made by Pierre Boulez and the Cleveland Orchestra. This taut, hard-edged recording, in controlled conditions and crisp digital sound, seems like it would be a contradiction in musical terms. It is led by a composer-conductor who is on the record as not being a particular admirer of Berlioz, seemed intent on making the point that the music written in this work was far ahead of its time. And he's right. Berlioz set the template here for a lot of French romantic music that followed, and his influence can be heard as far forward as works like Ravel's La valse and the ballet scores of Igor Stravinsky.

The Cleveland players take a crisp and modern approach to this score, only occasionally opting for period sound for certain effects. Most notable are the surging strings and winds in Reveries-passions, the first movement, and the glittering harps that adorn Un bal. With slow tempos, Boulez achieves a kind of existential loneliness in the slow movement, as the piping shepherds anticipate the bleak third act of Wagner's Tristan. The passage of the March to the Scaffold where the clomping strings are repeatedly interrupted by a merry band of brass players (complete with the blatting of the ophicleide) points the way forward to the controlled musical anarchy of Strauss' Till Eulenspiegel and Stravinsky's Petrushka.

In the final movement, Boulez emphasizes the horrifying transformation that Berlioz wreaks on the idée-fixe. His orchestra grimaces, leaps and leers where it first capered and whirled. Any possible love left between the Artist and his intended is obliterated by the grim tones of the Dies Irae and the capering woodwind section, which itself plays a fairground parody of that medieval hymn. It is as if the demonic laughter cannot control itself. The finale, which combines the now twisted and thoroughly wrecked Dies Irae idea with the idée-fixetheme that has coursed throughout the five movements. These two twisted ideas battle like wrestling snakes, creating an unwholesome gestalt that surges, rises and clatters to an apocalyptic finish. Music would never be the same.

Did you enjoy this review? Then why not pop over to Superconductor's Patreon page and support the cause of independent arts journalism today.