Maurizio Pollini plays with the New York Philharmonic.

by Paul J. Pelkonen

|

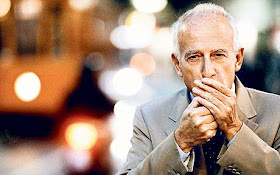

| Smokin': Maurizio Pollini lit up the Philharmonic on Friday night. Photo © 2015 Deutsche Grammophon/Universal Music Group. |

Mr. Pollini is a living legend, a pianist with impeccable chops and a habit of offering cool and accurate interpretations of a wide repertory from Bach and Chopin to Schoenberg. His withdrawn demeanor and sweet singing tone have made him more than a cult figure, he has been a superstar for more than five decades since winning the International Chopin Competition in Warsaw in 1960. For this concert, he would offer Chopin's E Minor Concerto with music director Alan Gilbert on the podium.

Mr. Gilbert opened the proceedings with Hector Berlioz' Le Corsaire overture, a little-heard piece that went through a number of excruciating revisions (and title changes) in its birth. Here, the massive orchestra seemed to lurch and lumber when there should have been rhythmic snap, and the waves of brass and string surged in an unpredictable and reckless manner. On the podium, Mr. Gilbert navigated this perilous ocean without a score, finally steering the work with a mighty breaking of the waves.

The great ship steered into more placid (and popular) waters next: Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet Fantasy-Overture. Last heard at a Philharmonic parks concert, this famous set of impressions from the Shakespeare play suffered too, with stiff, angular tempos in the early string passages and a sense of disjoint in the brass section. The woodwinds were the saving grace, with eloquent solos in the double reeds (bassoon, oboe, English Horn) bringing the lovers' plight into much needed focus.

Mr. Pollini took the stage at last, walking onto the stage with his shoulders bowed. He sat on the piano bench and went through a protracted adjustment, fiddling with the height of his perch even as Mr. Gilbert (working from a score at last) led the lengthy orchestral exposition that opens the first movement. And at last, he entered, his tone supple and a needed center of calm in this turbulent evening. However, he and Mr. Gilbert seemed to be struggling throughout this movement for control of the piece, with the piano pulling the work back toward its correct tempo before the wayward orchestra answered.

Happily, that conflict ceased in the central slow movement, which was placid and smooth as the first had been stormy. Mr. Pollini played the main theme with legato and limpid tone, the piano a silvery glow on the gentle waves of orchestral sound. This movement was nearly perfect, the high standard that one expects from this artist and this orchestra, glowing and rolling forth with a subtle, gentle grace.

The finale of this concerto is tricksome, a Rondo that emerges from a dancing figure for the right hand. Here, it was Mr. Pollini's speed and dexterity that were thrust firmly into focus, skating through the cadenzas with speed and grace. The orchestra too seemed to settle into the repeated theme, with the trumpets ringing out and the cellos supplying a firm rhythmic anchor. The artist, met with tumultuous applause from his adoring fans, took no encore.